Flooding at a retail park in Leeds during December 2015

Flooding at a retail park in Leeds during December 2015New figures released by the Association of British Insurers (ABI) suggest that the economic losses from flood and storm damage over the last couple of months will exceed those from two years ago during the wettest winter on record.

The ABI estimates that its members will pay out about £1.3 billion for claims following a series of storms and heavy rainfall.

Calculations of the economic losses from the winter 2013-14 have been completed by the Environment Agency but have not yet been published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. In March 2014, the ABI indicated that insurance claims would cost £1.1 billion, including £446 million for businesses and homes that were flooded.

The bill for damage so far this winter will also exceed the estimated £600 million in losses caused by flooding in autumn 2012, but will be much less than the £3.2 billion cost (PDF) of summer floods in 2007.

The UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (PDF), which was published in 2012, concluded that losses from coastal and river flooding in England and Wales could rise from an annual average of about £1.2 billion today to between £1.6 and £6.8 billion by the 2050s.

Cause of the recent floods

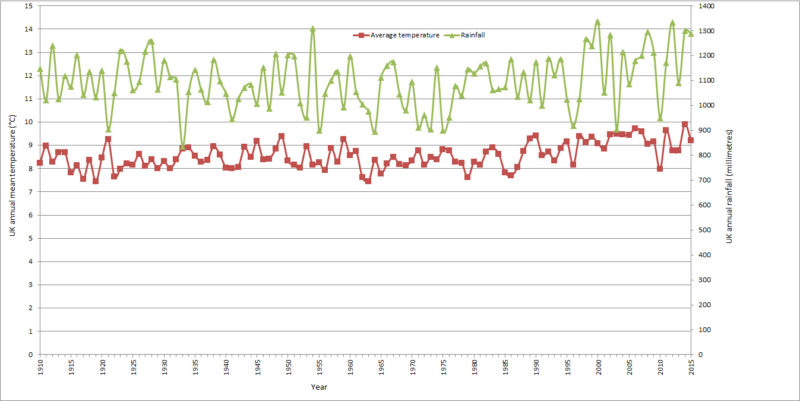

The floods in northern England and parts of Scotland over the past couple of months have been caused by record rainfall. Last month was not just the wettest December for the UK since Met Office records began in 1910, but the wettest calendar month of any year. Rainfall was well above average, by two to four times, in the west and north of the UK, but close to average over much of central and southern England.

By contrast, in winter 2013-14, much of Scotland and south-east England received rainfall amounts that were double the long-term average, with the most significant flooding in the Somerset Levels and Thames valley.

View larger version of this chart

View larger version of this chart

The journal ‘Hydrology and Earth System Sciences’ published a paper by Geert Jan van Oldenborgh and co-authors which concluded that the heavy rainfall which fell on northern England and Scotland during Storm Desmond between 4 and 6 December 2015 had been made 40 per cent more likely by climate change.

This record rainfall is part of a pattern, with six of the seven wettest years (TXT) on record in the UK all having occurred from 2000 onwards. Over the same period, the UK has experienced its eight warmest years (TXT). It is clear that climate change is making the UK warmer and wetter.

The Met Office has warned (PDF): “There is evidence to suggest that the character of UK rainfall has changed, with days of very heavy rain becoming more frequent. What in the 1960s and 1970s might have been a 1 in 125 day event is now more likely a 1 in 85 day event.”

A study by Dr Mari Jones and co-authors in 2012 concluded (PDF) that spring and autumn extreme rainfall events have increased in the UK, and longer duration rainfall events in summer and winter have increased in intensity.

Managing UK flood risks

There are three main sources of flood risk in the UK: coastal, river and surface water. Climate change tends to increase the risk of coastal flooding due to sea level rise, and to increase the risk of river and surface water flooding through heavier and more frequent rainfall events. The UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (PDF) estimated that about 6 million residential and non-residential properties in the UK are exposed to some level of risk of coastal, river or surface water flooding.

It has been suggested that the risk could be limited by preventing any further development on floodplains. However, this is not feasible as coastal and river floodplains cover large parts of the UK, and many of its cities and towns, including London, are built on floodplains.

However, flood risks can be managed in a number of other ways, for instance by restricting development in the areas of highest flood risk, by building and maintaining flood defences, by improving drainage, and by designing buildings to be ‘flood-resistant’ (ie buildings that suffer minimum damage when they are flooded).

Many businesses and households also manage the risk of losses due to flooding through insurance. The UK is different from most other countries because flood insurance is widely available. There has been a tradition for the premiums for flood insurance for households in the highest risk areas to be implicitly subsidised by other policy-holders. In 2016, a new scheme, Flood Re, will be introduced to explicitly provide these subsidies for homes built before 2009, with the aim of phasing them out within 20 to 25 years. When the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs initially proposed the scheme, it did not take into account the impact of climate change (PDF) on flood risk.

In its annual progress report to Parliament (PDF) in June 2015, the Committee on Climate Change pointed out that the UK Government’s investments in flood defences were insufficient to take account of the impacts of climate change and other factors. It stated: “Over the last four years there has been underinvestment in flood and coastal risk management in England, totalling more than £200 million. Due to this underinvestment, expected annual flood damage will be higher now than it was in 2010.”

The Committee recommended that the Government should develop a strategy to address the increasing number of homes in areas of high flood risk, with the ‘Flood Re’ subsidised flood insurance scheme playing a central role”. However, in its response (PDF) in October 2015, the Government rejected this advice on the grounds that it “would not be appropriate at this time”.

Following the flooding caused by Storm Desmond, the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Elizabeth Truss, announced the creation of a National Flood Resilience Review to “better protect the country from future flooding and increasingly extreme weather events”. The results of the review are due to be published in summer 2016.